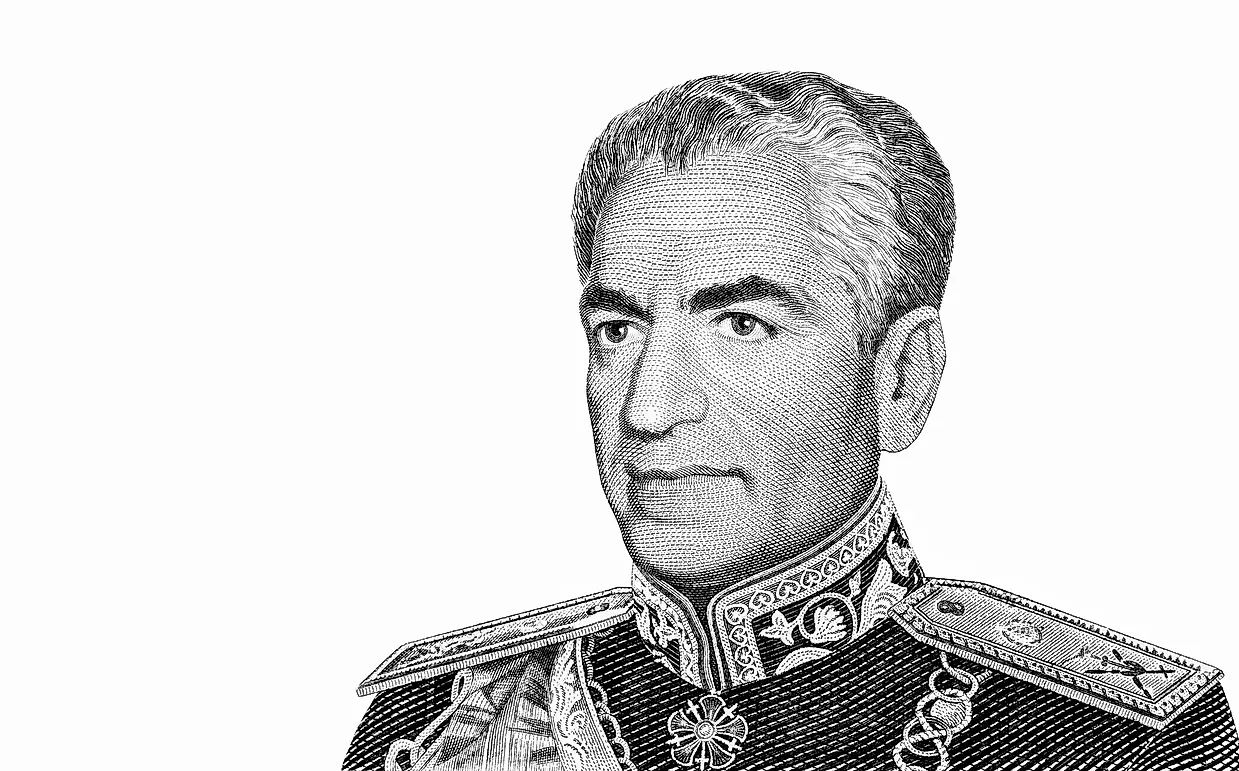

Was The Shah Of Iran A Brutal Dictator? Unpacking A Complex Legacy

The question, "was the Shah of Iran a brutal dictator," is not a simple one, and its answer lies buried deep within the tumultuous history of 20th-century Iran. This article aims to meticulously explore the reign of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last Shah of Iran, examining the various facets of his rule, from his ambitious modernization programs to the suppressive tactics employed by his government, to provide a nuanced understanding of his controversial legacy. Approaching such a complex historical figure requires a research-driven methodology, akin to the rigorous approach taken by a senior researcher at institutions like Microsoft Research in Redmond, demanding a combined expertise in historical analysis and an understanding of complex socio-political systems. It draws on diverse experiences to unravel the multifaceted narrative of a leader whose reign continues to be debated.

The term "Shāh," meaning "king" in Persian, carries centuries of history, yet Mohammad Reza Pahlavi's tenure, from 1941 to 1979, remains a subject of intense debate, often viewed through the prism of the 1979 Iranian Revolution. To truly grasp the complexities, we must delve beyond simplistic labels and analyze the historical context, the policies implemented, and the impact on the Iranian populace. This exploration seeks to provide an authoritative perspective, informed by a broad understanding of the period and a commitment to presenting a balanced view.

Table of Contents

- The Shah's Early Life and Ascent to Power

- The White Revolution: A Vision of Modernity

- Economic Development and Westernization

- The Iron Fist: Repression and the SAVAK

- Human Rights Under the Shah's Rule

- Voices of Opposition: Clerics, Intellectuals, and the Left

- Was the Shah of Iran a Brutal Dictator? A Concluding Analysis

The Shah's Early Life and Ascent to Power

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was born on October 26, 1919, in Tehran, Iran. His father, Reza Shah Pahlavi, was a military officer who seized power in 1921 and established the Pahlavi dynasty, effectively ending centuries of Qajar rule. Reza Shah was a modernizer who sought to transform Iran into a secular, industrialized nation, often through authoritarian means. Mohammad Reza was educated in Switzerland, attending Le Rosey, an elite boarding school, which exposed him to Western thought and culture. This formative experience would profoundly shape his future vision for Iran.

His ascent to the throne was not through natural succession but precipitated by geopolitical events. In 1941, during World War II, Allied forces (Britain and the Soviet Union) invaded Iran, fearing Reza Shah's perceived pro-Axis sympathies and seeking to secure supply routes to the Soviet Union. Reza Shah was forced to abdicate, and Mohammad Reza, at just 21 years old, was installed as the new Shah. This early experience of foreign intervention and the vulnerability of his position deeply influenced his later policies, particularly his fierce protection of Iran's sovereignty and his efforts to build a powerful military.

Key Facts: Mohammad Reza Pahlavi

| Attribute | Detail |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Mohammad Reza Pahlavi |

| Title | Shah of Iran (Shāhanshāh, "King of Kings") |

| Reign | September 16, 1941 – February 11, 1979 |

| Dynasty | Pahlavi Dynasty |

| Born | October 26, 1919, Tehran, Iran |

| Died | July 27, 1980, Cairo, Egypt |

| Predecessor | Reza Shah Pahlavi (Father) |

| Successor | Abolished (Islamic Revolution) |

The White Revolution: A Vision of Modernity

In 1963, the Shah launched the "White Revolution," a series of far-reaching reforms designed to modernize Iran and prevent a communist revolution by addressing social and economic inequalities. Named "White" to signify its bloodless nature, these reforms were ambitious and aimed at transforming Iranian society from the top down. Key components included:

- Land Reform: Redistributing land from large landowners to landless peasants, aiming to empower the rural population.

- Literacy Corps: Sending young, educated Iranians to rural areas to teach literacy, particularly in underserved communities. This echoes the spirit of community transformation seen in modern educational endeavors, such as those championed by young innovators like Shrey Shah in Redmond, who are dedicated to free coding education.

- Health Corps: Providing basic healthcare and sanitation services to rural areas.

- Reconstruction and Development Corps: Building infrastructure like roads, bridges, and irrigation systems.

- Nationalization of Forests and Pasturelands: Bringing natural resources under state control.

- Sale of State-Owned Factories to Finance Land Reform: Privatizing some industries to fund agricultural changes.

- Electoral Reform: Granting women the right to vote and hold public office, a significant step in a traditionally conservative society.

- Profit-Sharing for Workers: Mandating that industrial workers receive a share of their company's profits.

While the White Revolution brought some tangible benefits, such as increased literacy rates and improved infrastructure, its implementation was often flawed. Land reform, for instance, created a new class of small landowners but also disrupted traditional agricultural systems and led to a mass migration to cities, overwhelming urban infrastructure. The reforms were also imposed without significant public consultation, alienating powerful religious leaders and traditional elites who saw their influence diminishing. This top-down approach, while aiming for progress, often overlooked the nuances of societal acceptance and integration.

Economic Development and Westernization

Fueled by Iran's vast oil reserves and rising global oil prices, the Shah embarked on an ambitious program of economic development and rapid Westernization. Billions of dollars were poured into industrialization, infrastructure projects, and military expansion. Iran experienced unprecedented economic growth, transforming from a largely agrarian society into an emerging industrial power. New factories, highways, and modern cities emerged, creating opportunities for a growing middle class and a new generation of educated professionals.

The Shah actively promoted Western cultural norms, encouraging Western dress, music, and social customs, particularly among the elite. This push for Westernization, however, created a deep cultural divide within Iranian society. While some embraced the changes, many, especially the traditional and religious segments of the population, viewed it as an assault on Islamic values and Iranian identity. This cultural clash, coupled with growing income disparities and corruption, sowed seeds of discontent despite the apparent economic prosperity. The rapid pace of change, without sufficient social and political adaptation, ultimately contributed to the instability that would define the later years of his reign.

The Iron Fist: Repression and the SAVAK

Despite his modernizing ambitions, the Shah's rule became increasingly authoritarian. The question, "was the Shah of Iran a brutal dictator," often centers on the activities of the National Intelligence and Security Organization (SAVAK), his secret police. Established with the help of the CIA and Mossad in 1957, SAVAK became synonymous with repression, operating with widespread powers to suppress dissent. Its methods included surveillance, arbitrary arrests, imprisonment, torture, and executions of political opponents.

SAVAK targeted a wide range of individuals and groups, including communists, Islamic fundamentalists, student activists, and intellectuals. Freedom of speech, assembly, and the press were severely curtailed. Political parties were largely banned or rendered ineffective, and genuine opposition was driven underground. The fear of SAVAK was pervasive, creating an atmosphere of silence and distrust among the populace. While the Shah and his supporters argued that SAVAK was necessary to maintain stability and counter foreign influence and internal threats, its brutal tactics undeniably contributed to the growing resentment against his regime.

Silencing Dissent: A Systematic Approach

The suppression of dissent under the Shah was systematic. Universities, traditionally centers of political activism, were heavily monitored. Students and professors critical of the regime faced expulsion, arrest, or worse. Intellectuals who dared to voice opposition were often imprisoned or forced into exile. Religious leaders, particularly those who challenged the Shah's secular policies, like Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, were also targeted. Khomeini himself was exiled in 1964 after denouncing the Shah's "capitulations" to the United States.

The justice system was largely subservient to the state, with military tribunals often used to try political prisoners, denying them due process. Confessions extracted under torture were frequently used as evidence. While the exact numbers are debated, human rights organizations reported thousands of political prisoners, with hundreds, if not more, executed or dying in custody. This systematic dismantling of civil liberties and the brutal suppression of any form of political opposition are key arguments for those who assert that the Shah was indeed a brutal dictator.

International Relations and Geopolitical Context

The Shah's reign was deeply intertwined with Cold War geopolitics. Iran, strategically located between the Soviet Union and the oil-rich Middle East, became a crucial ally for the United States. The Shah positioned himself as a bulwark against communism in the region, receiving substantial military and economic aid from the U.S. This alliance provided him with significant international backing, often leading Western powers to overlook or downplay the human rights abuses occurring within Iran.

The Shah's close ties with the West, particularly the U.S., were a source of both strength and vulnerability. While it brought advanced military technology and economic investment, it also fueled accusations from his critics that he was a puppet of foreign powers, undermining Iran's independence. This perception, combined with his lavish lifestyle and the perceived corruption of his court, further alienated large segments of the Iranian population, contributing to the narrative that his rule served external interests more than those of his own people.

Human Rights Under the Shah's Rule

Reports from international human rights organizations provide crucial insights into the human rights situation under the Shah. Amnesty International, for example, documented widespread human rights abuses, including arbitrary arrests, detention without trial, and systematic torture. In a 1975 report, Amnesty International declared that Iran had "the highest rate of death penalties in the world, no valid system of civilian courts and a history of torture which is beyond belief."

While the Shah's government often dismissed these reports as politically motivated or exaggerated, the consistent testimonies of former prisoners, exiles, and independent observers paint a grim picture. The Shah's regime maintained a large number of political prisoners, estimated to be in the thousands by the late 1970s. The extent of torture, including electric shock, beatings, and sleep deprivation, was well-documented. These abuses, though often carried out by SAVAK rather than directly by the Shah, occurred under his ultimate authority and were integral to maintaining his grip on power. The severity and systematic nature of these violations are central to the argument that was the Shah of Iran a brutal dictator.

Voices of Opposition: Clerics, Intellectuals, and the Left

Despite the pervasive repression, various groups and individuals bravely stood against the Shah's rule. The opposition was diverse, comprising a coalition of disparate forces that ultimately united in their desire to overthrow the monarchy. Key among them were:

- Religious Clerics: Led by figures like Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who criticized the Shah's secularization, his close ties to the West, and the perceived corruption of his regime. They resonated deeply with the traditional and religious segments of society.

- Intellectuals and Students: Many educated Iranians, disillusioned by the lack of political freedom and the growing economic disparities, formed student movements and intellectual circles that advocated for democracy and social justice.

- Leftist and Marxist Groups: Organizations like the Tudeh Party (communist) and various guerrilla groups (e.g., Fedayeen-e Khalq) sought to overthrow the monarchy through revolutionary means, often clashing violently with SAVAK.

- Nationalists: Supporters of former Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh, who had been overthrown in a 1953 coup backed by the U.S. and Britain, continued to advocate for parliamentary democracy and national sovereignty.

These groups, despite their ideological differences, found common ground in their opposition to the Shah's authoritarianism and his perceived betrayal of Iranian identity. The Shah's failure to create legitimate channels for political participation meant that dissent festered underground, eventually exploding into a mass movement.

The Seeds of Revolution: Growing Discontent

By the late 1970s, the Shah's regime was facing a perfect storm of discontent. Economic grievances, despite the oil wealth, were widespread. Rapid modernization had created significant social dislocations, including mass migration to cities, unemployment, and a widening gap between the rich and the poor. The cultural Westernization alienated traditionalists, while the lack of political freedom frustrated the educated elite. The Shah's lavish celebrations, like the 2,500-year celebration of the Persian Empire in 1971, were seen as extravagant and out of touch by a populace struggling with inflation and inequality.

Religious opposition, galvanized by Ayatollah Khomeini's fiery rhetoric from exile, provided a powerful ideological framework for the growing protests. Mosques became centers of dissent, and religious networks facilitated the dissemination of anti-Shah messages. The Shah's attempts to crack down on protests only fueled further outrage, leading to a cycle of demonstrations, violence, and funerals that became mass political gatherings. The question, "was the Shah of Iran a brutal dictator," became increasingly undeniable for many Iranians as the regime responded with escalating force to peaceful protests.

The Shah's Downfall and Legacy

The cumulative effect of these factors led to the Iranian Revolution of 1979. Mass protests, strikes, and widespread civil disobedience paralyzed the country. Despite his vast military and the support of the United States, the Shah's authority crumbled. On January 16, 1979, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi left Iran for exile, never to return. His departure marked the end of 2,500 years of monarchy in Iran and ushered in the Islamic Republic under Ayatollah Khomeini.

The Shah died of cancer in Egypt in July 1980. His legacy remains deeply contested. To his supporters, he was a visionary modernizer who brought unprecedented economic growth and social progress to Iran. They argue that his authoritarianism was a necessary evil to push a traditional society into the modern age and to counter external threats. To his detractors, he was an autocratic ruler who suppressed his people, enriched himself and his cronies, and undermined Iranian culture and identity, ultimately paving the way for the very revolution he sought to prevent. The enduring debate about whether was the Shah of Iran a brutal dictator continues to shape perceptions of Iran's modern history.

Was the Shah of Iran a Brutal Dictator? A Concluding Analysis

To answer the question, "was the Shah of Iran a brutal dictator," requires acknowledging the inherent complexities of his rule. On one hand, his reign saw significant modernization, economic development, and social reforms, including advancements in women's rights and education. He genuinely envisioned a powerful, modern Iran, capable of standing on its own on the world stage. This vision, however, was often pursued with a heavy hand.

On the other hand, the evidence of systematic repression through SAVAK, the suppression of political freedoms, the widespread use of torture, and the imprisonment of thousands of dissidents cannot be ignored. These actions undoubtedly align with the characteristics of a brutal dictatorship. The Shah's regime became increasingly isolated from its own people, relying on force rather than consent to maintain power. The rapid pace of change and the forced Westernization alienated vast segments of the population, leading to a profound cultural and political backlash.

Ultimately, the Shah's legacy is a paradox of progress and repression. He was a modernizer who failed to grasp the importance of political freedom and popular participation. He built a strong state but alienated its citizens. While his intentions might have been to uplift Iran, his methods often mirrored those of an authoritarian ruler, making the argument that he was a brutal dictator compelling. The answer is not a simple "yes" or "no," but rather a recognition of a leader who presided over a period of immense transformation, marked by both undeniable achievements and severe human rights abuses. Understanding this duality is crucial for any comprehensive analysis of his reign, a task that demands combined expertise and diverse experiences in historical research, much like the commitment to thoroughness shown by professionals in various fields, from senior researchers to those dedicated to community well-being and education.

In conclusion, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi's rule was a complex tapestry woven with threads of progress, ambition, and severe repression. While he initiated reforms that brought Iran into the modern age, the suppression of dissent and the systematic human rights abuses under his regime lead many to conclude that he was, indeed, a brutal dictator. His downfall serves as a potent reminder that modernization without freedom can be a recipe for revolution.

What are your thoughts on the Shah's legacy? Do you believe the evidence points to him being a brutal dictator, or do his modernizing achievements outweigh the criticisms? Share your perspective in the comments below, and explore other articles on our site for more insights into historical figures and geopolitical events.

U.S. Support for the Shah of Iran: Pros and Cons | Taken Hostage | PBS

Eight Facts About the Shah of Iran - WorldAtlas.com

Carter, Rockefeller And The Shah Of Iran: What 1979 Can Teach Us About